- Home

- Cyn Vargas

On the Way

On the Way Read online

ON THE WAY

ON THE WAY

Stories

CYN VARGAS

Tortoise Books

Chicago, IL

SECOND EDITION, SEPTEMBER, 2021

PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED BY CURBSIDE SPLENDOR

Copyright © 2021 by Cyn Vargas

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Convention

Published in the United States by Tortoise Books

www.tortoisebooks.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-948954-55-6

This book is a work of fiction. All characters, scenes and situations are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

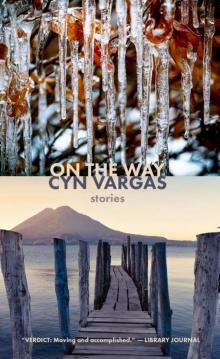

Cover photograph of icy leaves by Kateryna Mashkevych. Cover photograph of a dock leading out into Lake Aititlan in Guaremala by Oliver Colthart. Licensing per standard Shutterstock agreement. Cover Design Copyright © 2021 by Tortoise Books.

Tortoise Books Logo Copyright ©2021 by Tortoise Books. Original artwork by Rachele O’Hare.

Para Mis Abuelos

CONTENTS

GUATE

NEXT IN LINE

MYRNA’S DAD

HOW WE GOT HERE

ON THE WAY

THAT GIRL

AT THIS MOMENT

THE KEYS

ALL THAT’S LEFT

FLASH. THEN IT’S OVER.

THE VISIT

TIO PANZÓN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

GUATE

We were going to Guatemala for the first time since Mom left at eighteen. She often mentioned it as if it were a magical place with volcanoes that spurted lava and black sand that led to the ocean. After I graduated eighth grade, she took me as a present, saying I finally was old enough to enjoy the country. Had I known that would be the last time I’d ever see Mom and hear her voice, I would’ve done anything not to have gone.

At La Aurora International Airport, we rolled our bags past a throng of people who were holding flowers and balloons and stuffed animals. Mom’s aunt, Blanca, was supposed to meet us there. I had only seen her in pictures. She looked like a raisin in each one, short and dark and wrinkled.

“There she is,” Mom announced, taking my hand and leading me to her. Tia Bianca was even smaller than in the pictures. The bouquet of strange pink and orange flowers she was holding covered half of her.

Mom and Tia Blanca hugged and cried. A man with a giant straw hat came up to me and asked if I wanted to buy some mangos or a machete. I understood Spanish, but didn’t speak it well. I just smiled and shook my head and said, “Gracias.” He nodded and walked away.

“Oh, you’re so pretty,” Tia Blanca said. She had learned English at university. Even though we were the same height, she wrapped me in her arms. Her sweater smelled like vanilla.

On the cab ride in, Mom pointed out special places she remembered. “You see the cemetery? Right there. They bury people above ground and then paint the tombs bright colors. Death is not to be mourned. It’s a part of life.”

The cemetery was on top of a hill and the bright orange, blue, and pink squares looked like candy spilled from the sky.

“You see how the volcanoes look so close? They’re really miles and miles away. That volcano there still is active and spits out lava. Now, look over there. That volcano is active, but instead of lava it has water. It erupted a few decades ago and flooded the downtown area.”

We swirled through the streets of Guatemala City. There were so many honking cars that the sound was like a thousand geese in the road. Tia Blanca had fallen asleep, her chin against her chest, hands folded in her lap. Mom held my hand, something we hadn’t done since I was young. With the other, she pointed out more places—the school she had gone to that was just letting out, kids in blue uniforms running for freedom. She pointed at all the skinny stray dogs in the road, pointed at the street vendors: auto parts, bread, whole dead chickens hanging off a line, bananas, clothes, even goldfish. She smiled and squeezed my hand each time she said something.

“Selma, look,” she said, and pointed to a tiny shop with Selma’s Panaderia scrawled across the window in black paint. “I used to go there every week to get bread as a kid. I said when I had a daughter, I would name her Selma.”

The first week in Guatemala, Mom and I were inseparable. We stayed with Tia Blanca in a house where she lived alone. She started calling Mom and I las gemelas. It made my mom laugh that we were called twins.

We shared a bedroom with a white fan and a bed covered with a loud, dandelion-patterned blanket, which was stitched in different places with various colors of thread. Every morning, Mom and I would walk along many makeshift booths, where generations of women dressed in Mayan clothes of patterned hues tried to make a living. We would buy sweets stuffed with fruit, earrings made of feathers, and hair clips in shapes of flowers or bows that we’d use to keep our bangs out of our faces in the fierce sun. We’d pay with creased bills that had in the center a beautiful green bird with a red belly and long tail that Mom told me had been hunted into extinction. We bought bracelets with our names burned into a wooden piece surrounded by colorful beads. They made Mom’s too small for her wrist, but she still paid the lady, who had a baby sleeping in a sling across her chest. Mom gave her bracelet to me, and I wore both hers and mine together.

I took pictures of Mom and Tia Blanca: Mom’s arm over her aunt’s shoulder, both of them leaning against the door of Tia Blanca’s house, the windows covered in wrought iron bars that twisted like thorny stems.

We went to the beach, where the sand was black and the ocean was clear. I took a snapshot of Mom in her swimsuit, standing in water up to her calves. She stared into the endless water, the rose tattoo on her thigh glistening. She had gotten it when I was little, and told me that the rose was just for me. In summer, when Mom wore shorts, I would trace the rose’s outline with my fingers while we watched cartoons. I’d tell her that when I got older I was going to get a tattoo just for her, too.

The last picture I took of Mom was of her sitting on the front stoop and eating a guayaba, with a stray dog with ribs like hardened rainbows sprawled at her feet. When I took the picture, she laughed and said, “Selma. How many pictures is that now? Two thousand in a week?” She raised her guayaba, the reddish orange pulp inside shining in the morning sun.

The streets swarmed with cars, people, and even a couple of horses among the dogs.

“You feeling OK?” she said.

“My stomach hurts.”

She put her hand on my forehead. “Well, you don’t have a fever. Maybe it’s something you ate. You didn’t drink any milk, did you?”

I said nothing.

“Selma, I told you this is not like the States. Not to eat anything dairy.”

She asked Tia Blanca, who was waving at some passing neighbors, to make me some tea and to make sure I lied down.

“I’m going to pick up some groceries,” Mom said.

“Be careful, Adriana,” Tia Blanca said and went upstairs to boil the water.

“Don’t go to the beach without me,” I said, rubbing my stomach.

“When do I ever do anything without my twin?” She kissed my forehead and held my wrist. The bracelets rubbed against one another. “Go on up and lie down. I’ll be back soon.”

Her long curls swayed as she crossed the street. Her skin had darkened like toast in the few days we were there. She dodged speeding cars and slow dogs, turning when she got across to wave at me and point at the door of the house. I waved back. She smiled, and I could see her bright eyes despite all the sunshine. She turned the corner into a crowd of morning chaos.

Later that afternoon, I woke up f

rom my nap expecting to see Mom in the kitchen with Tia Blanca, drinking café con leche and eating the pastries we had bought that morning. But Tia Blanca was alone, her hands wrapped around a mug.

“Is Mom back yet?” I asked, feeling a little bit better.

“No. Not yet. Maybe the buses took long,” she said. But the wrinkles across her forehead deepened, and continued to do so as the hours dragged on.

By sunset, Tia Blanca had called every family she knew who had a phone, which wasn’t many. Then she called the police. An hour later, two pudgy men in gray uniforms arrived, with heavy badges tugging their shirts downward and matching thick mustaches. Tia Blanca sputtered that Mom was visiting from the States and would never have left me for that long. Then they began to question me. “You an American? Why did you come here?” They asked about jewelry Mom was wearing, and had I noticed anyone strange following us since we arrived. When they left, they took the only developed pictures of her that we had: the four we had taken together in a photo booth at the airport, printed on a single strip. In two of them we were making kissing faces; in one we were sticking out our tongues; and in another we were smiling, looking right into the camera lens. Tia Blanca cried and I went to bed.

That night, I dreamt of her. Mom sprawled in her bathing suit on the sand that was as black as her hair. The rose tattoo, faded crimson with two green leaves that curled at the ends, sprouted from her hip. The waves were rolling in, almost touching the tips of her feet that pointed toward the sky.

Without looking at me or moving her head, she said, “Selma.” Though it was a whisper I could hear her voice skipping along the sand as it made its way to me. I smelled the wet sand and the coconut oil that she had rubbed on her skin.

“Mama,” I said, though my lips were sealed shut and bled slowly when I opened them. I began to swallow the blood that came through my teeth, dripped down my chin and onto my bare feet.

“Selma.” Mom turned her head toward me this time. The sun grew brighter and her skin began to sizzle. I could hear it, inhaled it as it melted into the towel. Her hair fell away at the roots, exposing her white scalp. Her eyes were shut. I began to cry red tears and ran over to her, but each step caused her to melt more. Her skin stank like forgotten meat. Her screams echoed in my veins.

I stopped running and she stopped dying, and when she called my name again, I didn’t know if she wanted me to keep going.

It was strange to see Mom’s picture on the news. The anchors spoke quickly. The reporter wore too much makeup and tried to look concerned by forcing her brows into a V while she spoke of the American that went missing. I wanted to reach into the television and yank out that picture of Mom and me at the airport. They only showed the frame where we leaned into each other, each of us smiling. I wanted Mom next to me again.

Tia Blanca was on the phone with Tia Carmen and my grandma in the States. I spoke to Grandma once, but all she did was cry and I didn’t know what to say.

After a week, Mom was no longer on the news, and I was thankful. I hated those news anchors. They pretended to care, but when they switched to another story, they would laugh and forget all about her.

The room felt dreary even when in daylight. The sun highlighted the wilted flowers on the bedspread and the layers of dust on the fan. At night it was worse. The bed was too big, the pillow next to me stiff, Mom’s side of the bed untouched. I’d stare for hours at the fan, hearing its drone, feeling Mom’s name burned into my bracelet until I fell asleep.

In the mornings, Tia Blanca scanned the paper for news of Mom. Her hands shook.

“Mom’s coming back, right?”

“I don’t know. God said to never lie.”

After two months, the police lost interest. Sometimes I’d hear Tia Blanca on the phone talking about an article she had read in the paper about another body found that wasn’t Mom’s. She caught me listening once, scrunched up the paper, and told me to go to my room.

We went around the neighborhood, passing out fliers with Mom’s picture on them, but no one seemed to have any hope to give us. They just shook their heads and patted me on the back.

The volcanoes of lava and water both seemed to hide secrets from me. Every way I turned there they were, colossal and overpowering.

One morning after mass, where Tia Blanca and I prayed and lit another candle, I said, “Mom is coming back, right?”

“No, she’s not.” She put her soft hand on my face.

We were blocking the entrance of the church. People squeezed by us. The bells rang. My heart strangled on her words.

“I would love for you to stay, but you need to go back home, Selma. You belong back home. Your mom would have wanted that.”

“But Mom is coming back. I have to be here. I want to be here,” I cried.

“I’m old. I can’t take care of you. You’re going to go stay with your Tia Carmen and your grandma in Ohio.”

“I’ll take care of you,” I blurted, but I meant it. “I can’t leave.”

“She’s not coming back, Selma. Please. You look just like her. I can’t have you here anymore.” She grabbed my hand and I wanted to pull away from her, but didn’t. We walked in silence to her house.

“Tomorrow, a taxi will take you to the airport. I’m sorry,” she said, and unlocked the front door.

“But when she comes back,” I started to say.

She turned to face me. Her sweater was torn at one elbow, her gray hair was sparse, and I saw chestnut spots on her scalp.

“Do you know what happens to pretty women that go missing here? Pretty American women? She’s gone. Now, please.” She said something more, but a sob muffled her words, and she went into her room and shut the door.

The next day, she made a breakfast that I didn’t eat. She kissed me on the forehead and sat next to me in the taxi. My bag and Mom’s were in the trunk. We didn’t say anything. She peeked out her window and I peeked out mine. I heard her weep. The city was busy as always, but I felt detached from it all. We drove passed Selma’s Panaderia and I began to cry. The taxi driver didn’t say a word to either of us the whole hour to the airport. Instead, he played some music that I knew Mom would’ve liked.

At the airport, Tia Blanca leaned over and kissed my head. She stayed in the cab and I didn’t watch it drive away.

On the plane, I sat next to the window. On my other side, a fat lady slumped over and snored. I pressed my face against the glass and gazed at the green mountains and the ocean, Mom fading away behind the clouds.

I waited outside in the cold at the Dayton terminal with some airline employee dressed in all blue. “Have a good time on vacation?” he asked me.

I didn’t say anything. Tia Carmen was supposed to pick me up. I’d only seen her at Thanksgiving and Christmas back in Chicago when she would visit my grandma. Last year she hadn’t come at all, since Grandma had decided she would rather live with her daughter in Ohio than in some nursing home back in Chicago.

A black car drove up and honked. Tia Carmen looked older than the last time I’d seen her. Her curls were dark like Mom’s, but with blonde highlights. She wore huge sunglasses even though the sun wasn’t out. A neon pink scarf choked her neck. The employee patted me on the back and helped me put the bags in the trunk after Tia Carmen just popped it open without getting out of the car.

“You should start grieving for your mother,” she said as soon as I shut the car door.

The leather seat was cold against my legs. “What?”

“I said, ‘You need to start mourning your mother.’ ” She began driving with her left hand while punching the radio buttons with the other, shifting the music from Oldies to R&B to Spanish Rock. The rhinestones on her red plastic nails glittered in the evening sun.

“But Mom isn’t dead,” I said.

Tia Carmen’s lips were cracked. The car’s heater wasn’t turned on, and I blew into my hands. I could still smell Guatemala underneath my nails.

“She’s

dead, Selma,” she said, flatly, as if I had just asked her the time.

“No, she’s not,” I said, turning to look out the window. Kids in matching hats and gloves were making miniature snowmen in front of their houses, their moms watching from the windows.

“Don’t be foolish, Selma. She’s been missing for months, and in Guate, of all places. She’s dead, and the sooner you accept that, the sooner you can move on.”

I didn’t say anything. Mom used to tell me that since Tia Carmen was the youngest, Grandma had run out of love to give her.

“I’m cold,” I whispered under the changing lyrics and the changing shadows that cloaked her face as we drove down streets with giant leafless oaks. “She’s not dead,” I said a little louder, blowing breath onto my window, making hearts that faded as quickly as they appeared.

“You get to stay downstairs with your grandma,” Tia Carmen said as we pulled into her driveway. The petite house with its square front window was covered in snow. A weak light flickered in the basement window. Tia Carmen grabbed my bag from the trunk and walked in front of me. I rolled Mom’s suitcase across the sidewalk, brushing off snow as it collected.

“Mom, be careful with those candles,” she yelled when we walked in. The house was dark and cold. When she turned on the light, I saw that the mismatched loveseats and the fat TV were the only things in the living room.

“Your grandma’s downstairs. Tell her to show you where the extra blanket is,” she said. She pointed at a door whose frame had peeling white paint and hung like bark off a tree. “I’m working the second shift tonight. I made dinner. It’s on the stove if you get hungry.” And with that, she walked just a few steps into a room in the back and shut the door.

The house was silent except for the shower that had come on, and a kind of humming. The door to the basement squealed a bit when I opened it; the wooden steps cried out under my feet.

On the Way

On the Way