- Home

- Cyn Vargas

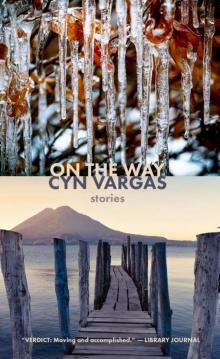

On the Way Page 5

On the Way Read online

Page 5

“You mad?” he said.

“Nope,” I said, and he put his arm around me again. Our shadows were one for a moment.

“Seriously, hip check!” He laughed again and we stopped underneath a tree. We were almost in high school, and we would be going to different ones. I knew that soon, things would change for us. New schools. New friends. New girls around him. Who knew if we would still hang out as much?

Nothing ever stayed the same for long. Mom and Dad proved that. I wanted to tell him how Grandma called me fat, how Mom was always working, how I’d been crying in my room a lot lately. I wanted to tell him this, but I didn’t want to lose him, too. I didn’t want to drive him away like Dad, so instead I didn’t say a word.

Underneath that tree, Benny turned his head one way, then the other, and finally kissed me. I heard the basketball fall to the ground, his hands on my hips. We opened our mouths, our tongues touched, and his soft lips met mine.

“I better get back before my grandma wakes up,” I said when it was over, and he smiled.

“Yeah. She’s crazy.”

When we got to my house, we stopped out front and we smiled again. “Let’s meet up tomorrow,” Benny said.

“OK.”

When I walked inside my house, Dad was sitting on the couch. Grandma sat next to him.

He was wearing the shirt that I had given him a few months back for Fathers Day, right before he left. It was so white against his dark arms. His hair was longer than it had been when he’d left, and wavier than I remembered. His glasses were perched mid-nose like always, and he pushed them up when he saw me. His eyes were wide, the amber speckles in them twinkling like they used to do when he’d tell me he loved me. He stepped forward, his arms rising up slowly like strings were lifting them. I noticed he wasn’t wearing his wedding ring.

“Lucia,” he said. Grandma held tight to his hand, not letting it go. “I’m sorry I left the way I did. It’s just—”

I didn’t let him finish. I ran out of the house and called after Benny, who waited for me to catch up. I pretended not to hear Dad shouting my name.

Benny waved at him. “Hey, your dad is back!” he said, and started to walk back toward my house.

“No!” I took his hand. “Please, Benny.” I didn’t need to say anymore. He knew from my eyes, my voice, in the way I touched his wrist that I had to go. He held onto my hand and we walked together toward his house.

“Why don’t you want to see your dad? I thought you would be happy,” Benny said. We sat on his couch. The house was quiet, his father out.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” I said, but I did. I wanted to tell Benny everything.

Instead of words, I began to cry, and he put his arm around me again.

“C’mon,” he said after a minute. He stood up and grabbed my hand. “You need to go talk to your dad.”

“No.”

“Lucia, if it were my mom who came back, I would talk to her. You’re lucky.”

“Fine,” I said.

He walked me back to my house.

“I have to be back before my dad gets home, but call me or come over later, OK?”

I nodded.

When I wandered into my house, Grandma was still on the couch. Dad next to her. He looked up from his hands when he heard me come in.

“Lucia. Please, let me explain,” he said. I followed him into the kitchen. We stood on opposite sides of the table. The sun was setting and all I could see was Dad cloaked in a soft glow.

“I don’t expect you to understand. Your mom and I, we just fought so much.”

“So you left? You fought with Mom, and you left without saying anything?”

I started crying, but didn’t bother wiping the tears away. I clenched my fists at my sides so tight, my knuckles hurt.

“I know you’re mad. I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have done that. I love you. I just had to go, and then time just went so fast.” He pulled out a chair and sat down. His put his elbows on the table and held his head in his hands.

“Did you leave us for another family? Is that it?” I shouted.

Tears began to roll down his cheeks. The glow was fading.

“No. It’s nothing like that. I’m sorry. I should have told you. I should have come sooner.” He went to say more, but cried into his palms instead.

“Does Mom know you’re here?”

He nodded. I crossed my arms, feeling my heart ram into my chest.

“I got my own place not too far away from here. I’m taking Grandma to live with me. She and your mom never got along anyway. Do you want to come see it? Your mom said it’s up to you.” He wanted me to say yes. I wanted to say yes, too.

“No.”

“Lucia, I didn’t leave because of you,” Dad said as I walked out of the kitchen, not turning back.

I hid under the covers until the house was quiet. I left my room, only hearing my footsteps. I threw the diet pills down the kitchen sink and washed them away. I pushed the chair Dad had sat in back underneath the table. I stepped out onto the back porch. On the step was a plate of mango, cut up in three perfect pieces. A small black bug crawled across the plate. I kicked it away. I wiped my eyes and looked up at the sky. There was no moon, no stars. I waited for Mom to come home.

THAT GIRL

That Girl used to be my Best Friend.

We double-dutched in seventh grade and beat the girls from room 209 to win that trophy made of wire hangers and cardboard, then went for pizza, grease sliding off the cheese like syrup. We chewed the rims of Styrofoam cups, spitting at one another and laughing. Then from our identical porches only a few feet apart, I could see the pink and black thread from your friendship bracelet coming undone. I waved goodbye as Henry rode by on his bicycle, throwing out a hello to you. And you threw out a smile at him, forgetting to wave back at me before you went inside your house.

That Girl in High School

The boy I like likes you with those curls that bounce as much as your chest. Not at my locker, but at yours, leaning against it, how his shoulder must feel, heavy and sweaty through his gym shirt the color of a ripe banana. You smirk and bend. He watches and you watch him watch and I don’t look that good bending, I’m sure. My shirt doesn’t come out like that on top, my skin not smooth like glass, your laughter like waves on a cloudless day and mine like a car that won’t start. He likes you for all this. And because of all this, he doesn’t notice when I’m not around.

That Girl with her Mom

It wasn’t hard for the wind to carry her yells into my house: “You’re too fat. A size six is two sizes too big. Look at me. I lost forty-five pounds eating fruit for five months. Your breasts are too big. Don’t wear tight shirts or boys will think you’re a whore. I already see lines around your mouth. Don’t laugh so wide and don’t laugh all wild. Laugh like me. You know? Pretty. Be pretty and life will be easier. Only hang out with the pretty girls. Ditch the one next door. It doesn’t look good, you hanging with her. If ugly girls don’t like you, that’s a good sign. And those curls. The ones with the frizz at the ends like they want to attack passerbys, the ones like your father. At least he had to shave his head to go over there. I’ll buy you a straightener. Your curls don’t know which way they want to go. I’ve seen better hair on a clown. Fix it, or what will the other girls think?”

That Girl in Class

I had to tell you: “I’m sorry. I didn’t know whether I should say anything, but I heard your ma yelling at you yesterday. Again. I think she forgets that her kitchen window faces ours and my ma never closes the window because she doesn’t believe in artificial air. Anyway, I know we aren’t close anymore like in grammar school, but I want you to know that the way she talks to you is wrong. I remember her always being a little mean. I heard about your dad being over there. My uncle is deployed too. Your dad will be back soon, you’ll see. Anyway, I wanted you to know that you shouldn’t listen to your ma. You’ve always been the pretty one, an

d you’re not fat, and if you just stopped hanging out with those phony kids I think you would be happier— Yes, Mrs. Hutchinson. I was just talking to her about homework. I better get back to my seat.” Then: “If you want to come over later, you know you can. I miss us hanging out.”

That Girl with That Boy

The burst of whispers in the hallway like a million sneezes say it went like this: “Come on. You know I love you. I know we’re young and all, but I’m always, always going to be here for you, baby. Don’t worry about it. My parents won’t be back for at least an hour. I knew in my heart the first time I saw you in gym class, I had to be with you. Let me kiss you right there. See? That was nice. You’re beautiful, girl. I bet all of you is beautiful. Why don’t you show me? C’mon. It’s OK. I won’t tell anyone at school. I promise.”

That Girl on my Porch

I found you there when I got home. Plopped in the same spot you used to be in when we’d watch the sunsets during the summer. I sat down next to you like we used to do, one step below near your knees. You began to cry, but still looked pretty there, although your eyes were as flushed as your face. “Why are you crying?” I looked at your bangs straight across your forehead, the curls drooping besides your eyes like moss. “School must be easy for you, though I know no one really knows your favorite color, or that you’ve had a crush on Henry since seventh grade or that although you don’t act like it in class, you’re smarter than a lot of the kids you hang out with. You don’t have to do anything with anyone you don’t want to do, you know?” You leaned into me, letting me hold you. I thought I heard you mutter something about being friends or being sorry, but that’s when your mother screamed out the window for you to get home. I never had a chance to ask you what it was you said.

That Girl and the Note

I found it folded in a triangle on my front step. It said: Thank you for yesterday. For talking with me. But let’s keep it between us. No one needs to know we talked or whatever. At school I passed by your locker, your hair straight like rows in church, you were talking to that boy, and the other girls laughed. You peeked at me and said nothing as I threw the note away in the garbage nearest you and made my way to class.

AT THIS MOMENT

When Grandpa called to tell me the news, I could hardly understand him because he was crying so hard. I ached for them both. My grandparents were the only two people I had in my life from my father’s side, and now one was gone.

Inside the funeral home, there was a sign on which Grandma’s name had been spelled in white letters. Quiet chatter came through the open door of the parlor. A group of small children horsed around in the corner, sucking on lollipops. Some adult hushed them with a quick, ineffective shhhh.

A wooden coffin sat at the front of the room beneath the glow of a bright light. Bouquets of flowers in vases had been propped on stands all around the coffin. Most of the people in the room sat in the chairs lined up in rows. Some drank coffee from small Styrofoam cups and spoke in hushed voices. From where I stood, I could only see Grandma’s head propped up on a pillow.

A large woman I didn’t know stopped before me. “My, aren’t you Miguel’s girl?” she asked. Two old men in black suits turned and peeked at us. “Not that you’re a girl anymore. Look at you, all grown.” She grabbed my wrist. “I’m sorry about your grandma, honey.”

The woman wore bright orange lipstick and her hair had been made stiff with hairspray. It was styled high and dyed an unnatural black. “Your daddy’s right over there. It’s nice how he came in from Florida.” She pointed to a huge bouquet of red and pink and white roses behind her.

From behind the bouquet appeared a man that I remembered too well. His hair had grayed, but I remembered that walk, the exaggerated sway from side to side. I remember his mouth, too, with its crowded teeth that stuck out so his lips didn’t meet when they closed. This man, who I had not seen in twenty years, was my father.

He didn’t come toward me, but stood alone, staring at the coffin. One of his hands was balled into a fist. He had gained weight since I had seen him last. His black jacket bunched around his shoulders. Suddenly, he turned away from the casket. His dark eyes met mine, and he mouthed my name.

I hurried past him to the coffin, searching the room for Grandpa, but couldn’t find him. I knelt before the coffin and put my hand on Grandma’s. It was like a doll’s. Her skin felt cold, her fingers were stiff. I closed my eyes and whispered, “Please make him go away.”

I felt everyone watching me. Kneeling in my long gray coat, I imagined I must have looked like a fallen statue. I stood up and kissed Grandma’s forehead. My lips felt like they were touching plastic.

I turned around. I could no longer spot my father. Maybe he left when he saw me. Maybe he was hiding somewhere. I finally saw Grandpa sitting down near the back with his head in his hands. The men sitting with him seemed relieved when I came over, and left us alone.

“Grandpa,” I said, and knelt next to him. The rough carpet scraped my tights. I rubbed his back, then slowly pulled his hands away from his face.

He looked at me, but didn’t see me. I wiped his eyes with my coat sleeve and when he finally noticed me, he pulled me into his arms. We began to sob.

“Here’s your water.”

I froze. The voice was empty, emotionless. I felt dizzy.

I stood up and turned to face my father.

“Hello, mija.”

The last big fight my parents had, I had snuck out of my room and tiptoed down the short hallway. I had slipped underneath my father’s desk, a small space that reeked of beer and was a nest of wires.

“Did you think I didn’t know about you and Christina?” Mom asked.

From beneath the desk, I watched my father’s fist smash the glass of the framed picture of me with my grandparents. Blood began to drip from his hand onto the floor. Then he turned on Mom.

I screamed. They both turned to look at me.

“Elena,” they said in unison. I ran upstairs. Some neighbors called the cops, and I stayed in my room and listened to Mom tell the officers nothing happened. After that, she told my father to move out, and then filed for divorce.

That summer brought my tenth birthday. My father decided it was time for a road trip to Florida, where I’d spend a week with him and his new girlfriend, who was already waiting for us in their new home.

“Mija, pass me some more,” he said, holding out his right hand as he drove. I reached into the gigantic box of Goldfish crackers and put a school of them in his hand. A while later, he pulled into a parking lot. We’d been driving all day. He told me to wait in the car while he paid for a room and got a key. The motel had two stories. All the doors to the rooms were the same faded yellow, all the curtains in the window the same shade of brown.

The sun was setting when my father came back to the car. He had lost weight since the divorce. Apparently when he and Christina moved to Florida, Christina left all her cooking skills behind. She had been my babysitter for a few months, and I guessed one day she’d probably end up being my stepmother.

“Let’s go, Elena.” He reached into the backseat and grabbed our bags. I followed him, carrying the pillow I had brought from home. The room had washed-out orange carpeting, and a trail of teeny cigarette burns. I went to turn on the lamp, but it didn’t work. With only one petite ceiling light, the room was dark. I noticed there was only one bed.

“Pop, where you going to sleep?” There wasn’t a couch or any other furniture he could sleep on.

“This is all they had. Now, go change into your pajamas. We’ve got to get an early start tomorrow.”

I went into the bathroom and tried not to touch anything because the sink had a brown circle of sludge in it and there was a dead fly near the door.

“C’mon. What are you doing in there?” Pop yelled. He sounded angry.

I opened the bathroom door. Pop was already in bed under the covers on one side of the bed. I went on the other side and

sat on top of the blankets.

“Why are you acting so weird?”

“I should call Mom and let her know we’re OK.”

“I called her from the payphone in the office when I got the key.”

I got under the covers. I couldn’t understand why I felt that afraid. I rolled onto my side near the edge of the bed.

“Goodnight,” he said and did the same. He didn’t bother to turn off the light.

3:33 flashed on the clock on the bedside table when I opened my eyes. The light was still on.

I could hear trucks passing on the highway. The TV was on. It was old, and the colors on the screen had an orange glow. Then, I felt Pop’s hand on my stomach. I felt him press his body into mine.

“Elena, are you sleeping?” His breath was hot on my skin.

3:34. I clutched my pillow tighter as his hand went beneath the elastic of my pajama pants, and then beneath the thin fabric of my underwear. His hands were rough, the skin hard.

“No, Pop.”

“Relax, sweetheart.”

I inhaled the stench of his breath. His fingers pushed inside me. I cried out and tried to swat his hand away, but he took it and placed it on himself.

I prayed he would stop. I squeezed my eyes and tears fell onto my pillow and I smelled Mom on it, my bedroom. Home.

He pulled away. I didn’t know whether I should pull up my pants or wait ’til he fell asleep. I was too scared to move.

At 3:41, the volume on the TV grew louder.

This time when he touched me he moaned.

“Stop crying,” he said, but I couldn’t. My sobs muffled his noises. I wished he would just beat me instead. Choke me like he did Mom. Kill me. I wanted to die.

On the Way

On the Way